The Life and Death of the Deadliest Man Alive

In the 60s and 70s John Keehan was one of the most notorious figures in American martial arts. He ran dojos and had sidelines in salons and porn shops. He took a pet lion cub for strolls by Lake Michigan. He trained minorities and caught flack for it, and after one fight—part of Chicago's "dojo wars" of the 60s and 70s—he was implicated in the death of one of his students. He was also a fierce self-promoter: comic-book readers might know him best as Count Dante, the persona Keehan used to sell membership in his Black Dragon Fighting Society, as well as a pamphlet, World's Deadliest Fighting Secrets, that promised to teach readers how to maim, disfigure, and kill.

Ever since his death in 1975, Keehan's life has been wrapped in rumor and parody, but Oak Park filmmaker Floyd Webb is striving to untangle truth from fiction. For the past year he's been working on a documentary about Keehan, The Search for Count Dante, inspired by his own experience in martial arts, as well as his brief acquaintance with Keehan. Growing up in the Harold Ickes Homes near Chinatown, Webb raised pocket money by collecting deposit bottles, scrubbing out Chinatown trash cans, and taking other odd jobs, and on September 4, 1964, he spent part of that hard-earned income to attend the Second World Karate Championship at the Chicago Coliseum. Numerous feats of martial-arts prowess were on display—board breaking, kata (patterns of techniques), sparring—and Webb recalls Keehan, the event's organizer, stalking the sidelines.

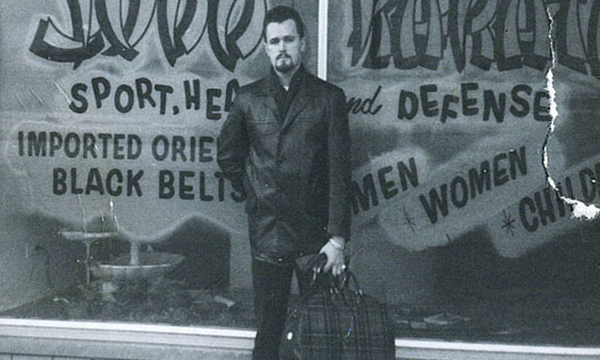

Keehan took a moment to chat with Webb and his friends—which impressed Webb not just because they were kids but also because they were black. Keehan became "Steve McQueen cool" to Webb after that. "He was a snappy dresser," Webb says. "He had a school on Rush Street. We used to go downtown with our various hustles when we ditched school, and we would always run into him."

Chicago had 13 dojos in 1964, and Keehan owned two of them: the Imperial Academy of Fighting Arts at 1020 N. Rush and Chicago Judo and Karate Center at 7902 S. Ashland. They were too far away and too expensive for Webb to attend, but he still pursued martial arts, checking out karate manuals from the bookmobile, studying untranslated pamphlets from Chinatown bookshops, and taking lessons from war veterans and immigrants from Hong Kong. He briefly competed in tournaments but eventually pursued a career in film: he studied photojournalism at NIU, founded the Blacklight Film Festival (a showcase for black filmmakers), and later worked as a producer on the films Daughters of the Dust and The World of Nat King Cole.

Webb revisited several old neighborhoods while working on the Cole documentary and ran into some friends from his karate days. One said he'd recently seen Count Dante on the street. So did another. A third said he'd actually talked to Keehan and claimed he was now living on the southwest side. "I said, 'You're hallucinating!'" Webb says.

He was sure Keehan was dead, but to make certain he pulled Keehan's death certificate. The self-proclaimed deadliest man alive, it explained, had died in his Edgewater condo from a bleeding peptic ulcer, probably brought on by years of stress and hard living. He was all of 36.

John Keehan was born in Beverly on February 2, 1939, to an affluent family: his father, Jack, was a physician and director of the Ashland State Bank, and his mother, Dorothy, occasionally appeared on the Tribune's society pages. He also had an older sister, Diane. They're all dead too, according to a cousin of Keehan's contacted by Webb. (The cousin did not respond to requests to be interviewed for this story.) In his teens Keehan attended Mount Carmel High School and boxed at Johnny Coulon's 63rd Street gym, and after graduating from high school he joined the marine reserves and later the army, where he learned hand-to-hand combat and jujitsu techniques.

By 1962, after the service, Keehan was teaching at Gene Wyka's Judo and Karate Center in Brighton Park and made occasional trips to Phoenix, Arizona, to study under Robert Trias, who had opened the first karate school in the U.S. and was head of the United States Karate Association. Training full-time, Keehan quickly earned his second-degree black belt and was appointed the USKA's midwest representative.

In the early 60s dojos were rough, bare-bones joints largely inhabited by cops, ex-soldiers, and assorted other tough guys. (Trias, who died in 1989, was an Arizona highway patrolman who'd studied karate while stationed in the Pacific during World War II.) But Keehan, wanting a bigger audience, began to organize tournaments that emphasized the flashier aspects of the martial arts; he appears on the cover of one tournament program smashing eight rows of bricks with his elbow. He was a savvy publicist, making sure the first event he organized, at the University of Chicago field house on July 28, 1963, got mentioned in the Tribune's "In the Wake of the News" column.

Keehan's early tournaments attracted a host of martial-arts luminaries—like Ed Parker, Jhoon Rhee, and a pre-Enter the Dragon Bruce Lee—as well as new students. James Jones, a 66-year-old retiree now living in Hazel Crest, signed on at Keehan's Rush Street school the day after he attended the U. of C. event. He studied with Keehan for three years and remembers him as an ideal instructor. "John was a person who focused on basics and fundamentals," he says. "He had excellent form and techniques." He also says that Keehan was one of the few men who could side kick or punch a brick in half, though at one event it took three strikes and Keehan wound up breaking five bones in his hand. Still, he showed up at the dojo the next day, his hand in a cast.

But Keehan also had an arrogant streak. "John was the type of person who enjoyed attention and being in the limelight," Jones says. "'If you're talking about me, then you know about me.' I thought that was a weakness: 'What can I do for myself instead of the art?'" Arthur D. Rapkin, a Milwaukee-area acupuncturist who studied under Keehan from 1965 to 1971, recalls Keehan's "chronic" arguing with other karate schools. His ideas for tournaments were the biggest problem. Unlike most other teachers, Keehan advocated full-contact matches—no safety equipment, no pulled punches.

"John was six-foot, well built, and looked like a bodybuilder," says Michael Felkoff, a friend of Keehan's now living in Las Vegas. "If you fucked with him, he was liable to hurt you."

Keehan charged students $20 a month—pricey for dojos at the time—and he gained a reputation for being one of the first white sensei in the country to accept nonwhite students. "Race never played a part in John's teaching," says Jones, who is black. Ken Knudson, a white student of Jones's who later founded the Sybaris couples' resort chain, was interviewed by Webb a week before he died in a plane crash last January. "John loved the martial arts," Knudson told Webb. "He loved it, he ate it, he breathed it. He was blind to race. It didn't matter."

Keehan claimed that race strained his relationship with Trias. In 1969 he told Black Belt magazine that in 1964 "the USKA didn't have any Negroes in the organization, except for mine, and Trias didn't like it one bit. . . . It's the truth. Of course, now he has no qualms about it, but at the time, that's the way it was." Trias, in a 1975 article, dismissed this as "nonsense." Jones, who trained under both men, believes that there probably was a de facto ban on minorities in the early days of the USKA but that the battle between Trias and Keehan likely had as much to do with control as with race. Whatever the reason, Trias expelled Keehan from the USKA in December 1964. Keehan was on his own.

Trias later said that Keehan "was given too much power too young and too fast," and in his mid-20s the future Count Dante did seem to start drifting off course. On July 22, 1965, Keehan and Doug Dwyer, a longtime friend and fellow instructor, were arrested after a drunken attempt to blow out a window at Gene Wyka's school with a dynamite cap. After they were apprehended, Dwyer was charged with four traffic violations; Keehan was charged with attempted arson, possession of explosives, and resisting arrest. He got two years' probation.

Around the same time Keehan bought a lion cub—a legal, if uncommon, practice before the 1969 Illinois Dangerous Animals Act—which he kept at his dojo on Ashland and walked around town like a dog. (He later sold it to the Lions Club of Quincy, Illinois.) In the summer of 1967 he promoted an audacious exhibition in which, as part of a tournament at Medinah Temple, a bull would be killed with a single blow. Keehan purchased a bull from the stockyards and drove it around town on the back of a flatbed truck festooned with signs announcing the event. He wouldn't perform the deed himself: he'd picked Arthur Rapkin, then a 19-year-old student, for the task.

Bull killing was the signature stunt of karate legend Mas Oyama, and Rapkin initially seemed game: in a Tribune article about the event (headlined "Karate Expert Thwarted as Bull Hitter"), he's quoted as saying that if the police prevented him from attacking the bull in the building, he would "kill it in the truck on State Street, if necessary." But after the seats were filled Keehan announced that the event had been shut down by the Chicago SPCA. In hindsight, Rapkin says, he believes Keehan and his associates never seriously considered staging the event. "They were probably just howling at this little Jewish kid from Milwaukee they were going to put up against this bull," he says.

That year Keehan legally changed his name to Juan Raphael Dante, telling people that he wanted to reclaim the royal title he lost after his parents immigrated to the U.S. in 1936, during the Spanish civil war. It's never been clear why a south-side Irish guy like Keehan decided he must be a Spanish count, or how he chose his new name (though Mount Carmel High School is located on Dante Avenue). Regardless, his new name and background came with a flashier stage presence. At a 1967 tournament held at Lane Tech, he arrived wearing a flowing cape and brandishing a cane capped by a lion's head; he'd dyed his hair jet-black and had a neatly trimmed beard, reflecting his new side gig in cosmetology. Also in 1967 he opened a salon, the House of Dante, at 2558 W. Superior in West Town. Rapkin recalls that Keehan recommended hairdressing to him as a profession; the flexible hours would let him pursue martial-arts training, and it wasn't a bad way to meet girls.

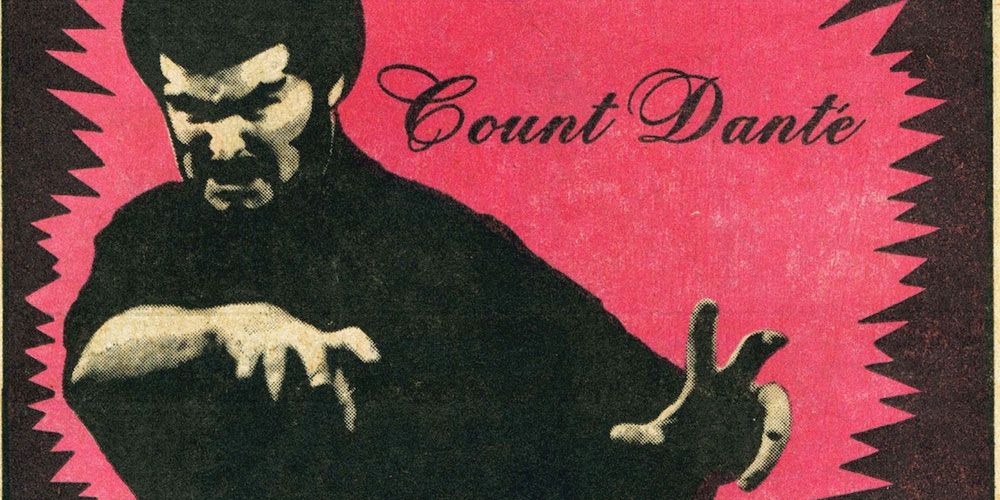

Suited up in his new persona, Keehan decided to make a play for national recognition. Inspired by kung fu dim mak, or "poison hand," strikes—which emphasize thumbing out eyes, flaying skin, fish-hooking lips, and suchlike—Keehan assembled the World's Deadliest Fighting Secrets pamphlet, which promised to teach readers his "dance of death," a rapid combination of attacks designed to leave your opponent in a writhing, bloody heap. Keehan advertised heavily in comic books, doing his damnedest to separate a generation of kids from their paper-route money:

Yes, this is the DEADLIEST and most TERRIFYING fighting art known to man—and WITHOUT EQUAL. Its MAIMING, MUTILATING, DISFIGURING, PARALYZING and CRIPPLING techniques are known by only a few people in the world. An expert at DIM MAK could easily kill many Judo, Karate, Kung Fu, Aikido, and Gung Fu experts at one time with only finger-tip pressure using his murderous POISON HAND WEAPONS. Instructing you step by step thru each move in this manual is none other than COUNT DANTE—"THE DEADLIEST MAN WHO EVER LIVED." (THE CROWN PRINCE OF DEATH.)

World's Deadliest Fighting Secrets was very much a Keehan vanity project. The pamphlet's first two inside pages were a sustained brag about the martial arts he'd mastered, his "Strikingly Handsome" looks, and his devotion to classical singing. Those were followed by photos of Keehan in a black silk gi, demonstrating techniques like "Groin Slap or Grab and Tear Off (often called 'Monkey Stealing a Peach')" on an uncomfortable-looking Doug Dwyer. It wasn't entirely hooey. "The 'dance of death' was overkill," says Massad Ayoob, a security expert who interviewed Keehan for Black Belt magazine in the 1970s, in an e-mail. "But it also taught that a single blow or attack could fail, thus inculcating the student with the principle of continuing to fight until he had won."

It's not known how many comic-book readers ponied up five bucks for a copy of the pamphlet, but Keehan's fortunes clearly grew—by 1969 he had opened three new Imperial Academies of Fighting Arts in the city. He also continued to hold full-contact tournaments, and his bad-boy rep began rubbing off on the larger Chicago martial-arts scene. Black Belt refused to cover Keehan's tournaments, and in 1969 it published a roundtable conversation in which several Chicago instructors laid into Keehan's tactics. Keehan claimed to have taught 60 percent of Chicago's karate instructors, to which Black Belt managing editor D. David Dreis replied, "Which is one reason why Black Belt didn't cover Chicago." One instructor described a Dante tournament he judged as an "amateur boxing match" and said he'd never judge another. Dreis wrote that Keehan's spectators "come to [his tournaments] to see plenty of blood spilled. Ofttimes they are disappointed; all too often, they get their money's worth."

On April 24, 1970, Ken Knudson got a call from a friend, Jim Koncevic. Koncevic explained that Keehan wanted to visit a rival dojo, the Green Dragon Society's Black Cobra Hall of Gun-Fu and Kenpo at 3561 W. Fullerton, to settle a beef with a member. Knudson asked what the dispute was about. "Oh, you know John," Koncevic said. "Over a broad or something." Knudson was still competing and training, but he took a pass, declaring a potential rumble "kids stuff."

The three men had been friends since the early 60s; Koncevic, Keehan's top student, ran his own dojo on the west side, the Tai-Jutsu School of Judo and Karate. "Jimmy was a battler," Knudson said. "He was notorious. He was legendary for getting into street fights, just mauling people."

Most accounts agree that Keehan did call the Green Dragons' dojo earlier that evening. In an article published a year later in Official Karate, he claimed that he and his students had received death threats and that he'd planned to "level their entire instructor force." To do it he called another friend, Michael Felkoff, and Koncevic; he described the latter in the article as an "animal as a fighter with a killer instinct." Today Felkoff says he was only called in to act as a mediator.

When Keehan arrived at Koncevic's dojo, he was dismayed to see that Koncevic had called in three of his younger students to join them. Keehan later described them dismissively: "Two . . . were only skinny kids who worked a whippy, snappy, and ineffective karate," and a third was a "short, pudgy clod." Still, he led the group to Black Cobra Hall.

According to a Tribune article, Keehan broke down the front door and found six Green Dragons inside. Felkoff, who arrived late, recalls that the Green Dragons were armed with Chinese weapons. Somebody—it's unclear who—made the first move, and accounts disagree about what happened next. According to Black Belt one of Keehan's men struck a Green Dragon member, Jose Gonzalez, in the eye with a nunchaku, while a Black Belt Times article says that Keehan himself attacked the instructor, lacerating his right eye badly enough that it required surgery at Belmont Community Hospital.

In every version of the story, Koncevic was ready to dance. According to the Tribune he struck one Green Dragon, Jerome Greenwald, from behind and began punching him. Greenwald grabbed a sword from the wall and stabbed Koncevic while trying to block a blow.

"All I saw was Jim in a big pool of blood," Felkoff says. "He was using his judo, trying to grab them, and he ended up getting stabbed."

Keehan shouted for everybody to stop fighting or he'd call the cops. Koncevic had enough life left to yell at everyone to "get the fuck out." He ran out the door and stumbled a few feet before falling. His three students had bolted and called the police. According to the Tribune, Greenwald, 20, was arrested and charged with murder; Keehan, 31, was charged with aggravated battery and impersonating a police officer. (No explanation was given for the latter charge.) Koncevic, 26, died on the sidewalk.

Keehan's attorney was Bob Cooley, who later worked for the Outfit until the late 80s, when he wore a wire for federal investigators in Operation Gambat. A mutual friend recommended him to Keehan; in his 2004 memoir, When Corruption Was King, Cooley recalls his first meeting with Keehan by describing his client as a tall, wild-bearded man wearing a yellow fishnet leotard and a purple cape. As for the trial itself, Cooley wasn't too worried. The state built its case against Keehan around the accountability statute, arguing that he bore responsibility for Koncevic's death. Cooley was prepared to assert that there was no way Keehan could have anticipated the swordplay that ensued at Black Cobra Hall.

In 1971 the judge in the case dismissed all charges but not before upbraiding both sides: "You're each as guilty as the other," Cooley recalls him bellowing. Though Keehan was acquitted, his name was blackened; interschool rivalries and after-hours grudge matches were common, but this was the first time anyone had died. Keehan offered a mea culpa in an Official Karate article. "I blame myself to a great extent for being responsible for us going over to the Black Cobra Hall in the first place and have gone through living hell because of it," he wrote. "My days of fighting at the drop of a hat have come to an end and challenges I will accept no more unless first attacked."

His vow was short-lived, though: Cooley recalls him beating up two men in a liquor store parking lot after they laughed at the bogus Spanish coat of arms on the door of his brown Caddy and assaulting another guy who called him a "fruit" in a bar. One night Cooley and Keehan had an argument, during which Keehan took a grazing swipe at his chin that put Cooley in such pain he felt his skin was "ripped off." Keehan immediately apologized and promised to make amends by showing him a trick: if Cooley got his pistol and fired at him, he'd catch the bullet.

Cooley kept his distance from Keehan after that, but he couldn't shake Count Dante entirely. By 1974 Keehan had a financial interest in a chain of adult bookstores and a car dealership. He eventually ran afoul of south-side boss Jimmy "the Bomber" Catuara, and Cooley was called in to intercede. Keehan, Cooley writes, paid 25 grand to Catuara and emerged unscathed, but the situation apparently gave him the connection with organized crime he'd been seeking for some time.

In the fall of 1974, Keehan was subpoenaed by the state's attorney and given a lie detector test about his possible role in the heist of more than $4 million from the headquarters of Purolator Security. A Tribune item from November says he was slated to appear before a grand jury with Catuara; it describes Keehan as "a former hairdresser who wears a cloak and calls himself Count Dante."

The experience seemed to shake Keehan, and by 1975 he was clearly unwell—Ayoob recalls him stumbling through one conversation before admitting that he was mixing booze and painkillers. He made a last attempt to revive his martial-arts career by hosting a tournament in Taunton, Massachusetts, on March 16. The karate world was unimpressed: a piece in Official Karate on the event, titled "Sunday, Bloody Sunday," characterized Keehan as looking bored and concluded that "whatever the reasons for this 'expo,' the resulting manifestation was trash."

In an interview with the Attleboro, Massachusetts, Sun Chronicle to promote the event, Keehan sounded resigned. "I want people to forget me," he told reporter Ned Bristol. He died two months later, on May 25, 1975.

Keehan was buried in an unmarked grave in Saint Joseph's cemetery in River Grove. His legacy is modest. Shortly before he died he helped his friend and protege William Aguiar set up a school in Fall River, Massachusetts, and appointed him his successor as Supreme Grand Master of the Black Dragon Fighting Society. Aguiar died in January of last year, leaving his son William Aguiar III in charge. In San Francisco, Bob Calhoun leads a band called Count Dante & the Black Dragon Fighting Society. Originally knowing little about Keehan outside of the comic-book ads, he invented an outsize stage persona that's part punk, part karateist, part motivational speaker, and wears leopard-print kimonos onstage. "What was funny was how much my portrayal turned out to be like the real Keehan in the first place," he says. The Aguiars have sent cease and desist orders to Calhoun, but nothing has been settled or gone to court.

Otherwise the person most interested in Count Dante seems to be Webb, who plans to finish the film next year and then shop it to festivals. He's logging his progress on a Web site for the film, thesearchforcountdante.com, which has attracted bits of archival material, including rare footage of Keehan in action. Webb imagines the film will reflect Keehan's era as much as the man himself. "It's the times," Webb says. "His story embodies every kind of macho popular culture bull crap. It's got discos and Rush Street and pet lions. . . . You can't write shit this good."

"He's dead and we're still talking about him," says James Jones. "He did what he set out to accomplish."